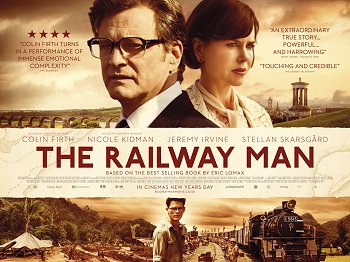

The Railway Man/

/ The Immigrant

(2013)

Of the three films that I’ve seen in the past week, two—The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Immigrant—have been hailed by critics whilst leaving me distinctly cold. The third—The Railway Man—received lukewarm reviews whilst leaving me in bits. That’s one of the many things that I love about the movies: we all see something different.

The Railway Man

Whilst Colin Firth may have won his Oscar for Best Actor courtesy of The King’s Speech, it is surely as Eric Lomax in director Jonathan Teplitzky’s outstanding The Railway Man that he has delivered his finest performance. He proves here—and not for the first time—that he can do more with his face in repose than many an actor can with a page of verbiage. Watching him, we imagine that we can actually understand what is going through his head; which is thankfully impossible— because very few people would be unfortunate enough to have suffered as Eric Lomax has.

When we meet him at the beginning of the film, it is 1980 and he just another middle-aged man on a train. As he strikes up a conversation with his fellow passenger, Patti (an excellent Nicole Kidman) he appears at first slightly eccentric. He is after all, if not a ‘train-spotter’ as he points out later, a ‘railway enthusiast’. Soon, though, Patti—and the audience—warm to his dry sense of humour:

“Back then Warrington was the only place to go for a suit of armour. It was like Savile Row for steel. And if you think that Warrington is impressive, just wait until we get to Preston.”

For the first twenty or so minutes, The Railway Man seems like a love story for older people culminating quickly in the two getting married. At this point, however, Patti discovers that Lomax suffers from terrifying panic attacks and learns from his friend Finlay (Stellan Skarsgård) that they are part of a group of survivors who had been prisoners of war to the Japanese and who had been forced to build the Thai-Burma railway for them under the most appalling conditions of depravation and torture. This was especially true for what we now know to be the deeply traumatised Lomax. We and Patti see how the men have come to be as they are over the course of captivating but brutal and extended flashbacks to 1942; whilst in the present Finlay intones with what seems to be a baffled sense of futility:

“When we surrendered, the Japs said we weren’t men; that real men would kill themselves or die of shame. But we said no, we’ll live to fight you. We’ll live for revenge. But we didn’t; we don’t live. We’re miming in the choir. We can’t love, we can’t sleep. We’re an army of ghosts.”

Based on the book by the real-life Eric Lomax, we see him make contact after more than three decades with the Japanese interpreter Takashi Nagase (Hiroyuti Sanada) who witnessed his torture but who now, to Lomax’s disbelief, is a guide on the very railroad that the prisoners had been forced to build. What happens when the two men meet is the final act in this truly powerful and moving film and certainly left this viewer emotionally drained and in tears. Yes, you read that correctly.

The screenplay is by Frank Cottrell Boyce and Andy Paterson, who necessarily compress some events; but the overall feeling is of having seen something very special, a film that is grim as hell and yet filled with hope and redemption.

Although released in 2013 The Railway Man is not only one of the best films I’ve seen this year, it is also one of the most important.

The Immigrant

Another film rooted in the past, and dealing a with a protagonist who is equally haunted by injustice, is James Gray’s film The Immigrant, from a screenplay by him and his co-scripter Ric Menello.

It is clearly a labour of love and the recreation of New York in 1921 is breathtaking. Yet I found it simply uninvolving. A Polish woman called Ewa (Marion Cotillard) arrives on Ellis Island with her sister, but is immediately separated from her as the sibling is carrying a contagious illness. She herself is saved from deportation by a pimp Bruno (Joaquin Phoenix) who becomes obsessed by her.

Unfortunately, so does his illusionist cousin Emil (Jeremy Renner) and as you might expect, tragedy unfolds.

Oddly enough, it’s not the hideously miscast Renner that throws the film for me; it’s Cotillard, whose performance has been greeted by ecstatic moans. I don’t get it. She is so dull, boring and accepting of what is thrown at her that I found it hard to believe one of these men would become unhinged by her, let alone two. In fact, I actually enjoyed her performance far better in The Dark Knight Rises, hardly one of my favourite films.

As I said at the top of this piece, that is what makes movies so wonderful for me: we can all look at the same story and take something different away from it. Of course, if you disagree with these two examples then I trust that you are aware that you are wrong and I’m right.

Recent Comments