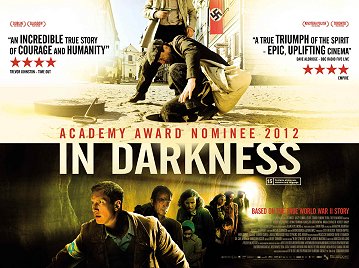

Notes from the Underground:

In Darkness

At his funeral, someone said, “It’s God’s punishment for helping the Jews”.

As if we need God to punish each other.

—-In Darkness (2012)

It is 1943 and in the town of Lvov, in Nazi-occupied Poland, sewer worker Leopold Socha (Robert Wieckiewicz) is making a reasonably comfortable fist of a bad situation by indulging in a bit of thieving on the side. He is a Catholic but he doesn’t have many qualms about fleecing the persecuted Jews of the ghetto either. Nor does he appear particularly moved by an appalling scene that he witnesses close to the very beginning of In Darkness: a large group of terrified women of all shapes and ages are being chased into a wood by Nazi thugs and murderers for the inevitable conclusion of a mass execution.

So he’s not a particularly noble or heroic guy, then. Which makes it not much of a surprise when, as the Germans decide to execute all the Jews of the ghetto, he finds himself helping a group of them only for mercenary reasons. Thus, when he leads them off to hide in the sewers that he knows so well it is a business transaction all the way. Well, at first. A few doubts begin to surface when he tries to justify the Catholic-Polish attitude towards Jews. To his wife Wanda (an excellent performance from Kinga Preis) he poses that golden oldie that makes no damned sense whatsoever: “The Jews crucified Jesus. It’s written in the Bible: ‘His blood be upon them and their children.’ The priest said so.”

Wanda is having none of this bullshit, though: “That’s just church politics. Just think about it. Jews are just the same as us. Our Lady was a Jew. Even Jesus.”

This last bit throws our Leopold for a minute. “Jesus was a Jew?” And he’s not the only Catholic Pole in the film who has a bit of a problem getting his head around that. [I have certain views on the insanity of all religions, from L. Ron Hubbard to Uncle John Smith so I won’t get into that. And please don’t tell me that Scientology isn’t a religion because it doesn’t seem any crazier to me to believe in Thetans from Outer Space than it does to believe that a guy who has been nailed up for three days before dying, can get up and rock around the joint again.]

In fact, despite the seeming simplicity of the plot the moral issues in this film are rather complex. Certainly none of the characters appears initially to be particularly likeable. These aren’t quietly suffering Jews, either, grateful for the help they’re getting. Rich Mr. Chigar (Herbert Knaup) isn’t too happy to be parting with his cash and there is quite a lot of whinging about living conditions—which are, after all, down a labyrinthine sewage system; but even though Leopold is having himself a nice earner out of the whole nasty transaction there is the little matter that if he is caught it is summary execution.

It is inevitable that this film will be compared to Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List but it is a triumph on its own merits. It is List written smaller and there are no really big dramatic scenes, but that is what makes the quieter ones all the more effective. I was struck by the sheer furtiveness throughout, especially in the lovemaking; and it is interesting that in the midst of this horror that sex is still important to them. Yet of course that makes perfect sense.

Then there is the scavenging for ‘souvenirs’ amongst the wreckage of the ghetto, which leads, ironically, to Leopold’s daughter playing with a couple of rag dolls that she calls “my Jews”, the term which her father has begun to use himself. There is the sense of constantly having to be on guard—even when buying extra food Leopold is treated with suspicion.

My favourite scene, however, is of the little girl singing quietly and the happy faces of the Jewish refugees as they look at her. Indeed, they are almost glowing. It is an extraordinary moment: beauty flowering amongst the rats and the shit of a sewer.

And Leopold’s reluctant transformation from mercenary money-grubber to genuine hero is subtly and unsentimentally done.

Music is used sparingly so it was with a lump in my throat that at one point I realised that Dido’s Lament by Purcell was playing very effectively on the soundtrack. [See below.]

I would estimate that around two thirds of In Darkness takes place underground, which on a couple of occasions makes it quite startling for the viewer when the camera hits open air again. For that reason it may be a little long at two and a half hours but it is still a film worth seeing.

It is directed by Agnieszka Holland and written by David F. Shamoon, based on the true story of the Jewish group who spent a staggering fourteen months underground. It is taken from Robert Marshall’s book In the Sewers of Lvov.

The version of Dido’s Lament that I have chosen is by the gorgeous Norwegian soprano, Sissel. I hope that you enjoy it.

[media url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrcneTn1IgY” width=”600″ height=”400″]

Recent Comments