No Fun Playing With Oneself:

The Lair of the White Worm

(1988)

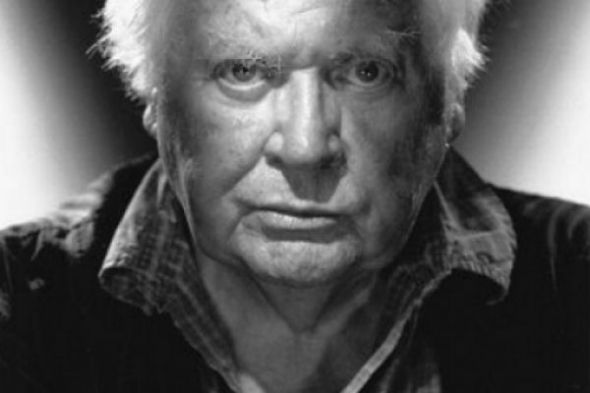

I recall a TV interview featuring director Ken Russell just after his 1988 film The Lair of the White Worm was released. It was based on the final novel from Bram Stoker, author of Dracula. “Did you know,” the interviewer helpfully mentioned, “that Stoker was dying of Bright’s Disease at the time?”

“Well, he certainly wasn’t too bright when he wrote it”, replied Russell with his usual lack of reverence.

Stoker had indeed been dying, as well as approaching insanity with frightening visions of serpents. He managed to just about hold it together until he had finished the book but it remains a mishmash even if the basic concept is fascinating; and of course Russell had been working out his own obsessions concerning such things as Christianity versus Paganism through his movies for years, so there was an appeal for him—especially as his own long-term project on a ‘Dracula’ film was going nowhere.

By this point in his career Russell’s heyday of classics such as Women in Love, The Music Lovers and The Devils was long behind him. Certainly he couldn’t command the kind of budget he had for Tommy and by God it shows with Lair. But for several years now Russell had been proving that what he lacked in funds he was more than able to make up for with flair and imaginative genius. Personally I doubt that I’d be able to hold a conversation with someone who didn’t get the sheer gleeful anarchy of this…this what? Horror-comedy? Who cares, don’t give it a label; it is what it is. It’s campy, it’s kitsch and yet viewed in the right light and with an open mind it can be quite eerie in its way and even give you a fair bit to think about.

It is set in a kind of washed-out part of England that seems to exist outside of time. A young Scottish archaeologist by the name of Angus Flint (Peter Capaldi) has been lodging with two sisters, Eve (Catherine Oxenberg) and Mary Trent (Sammi Davis) when he digs up the skull of some enormous animal. He knows that it can’t be a dinosaur relic because it is at the same level as some coins from a Roman settlement. Friendly in a platonic way with the girls is their aristocratic neighbour Lord James D’Ampton, played with wonderful stiff upper-lip jauntiness by a likeable pre-Four Weddings Hugh Grant. As soon as we learn that his ancestor is famous for having slain a creature known as the D’Ampton Worm centuries before we know what young Angus has unearthed.

If these four attractive people all behave in a way that is oddly sexless then one new character positively oozes with it. This is another neighbour, the Lady Sylvia Marsh who is none other than Amanda Donohoe looking as if she is relishing every moment of her scene-stealing character. Lady Sylvia has been in hibernation for the winter, just as any good snake should be but now she’s back and very interested in the skull, very interested indeed. Like it, Her Ladyship dates back to the time of that Roman settlement when some busybody nuns tried to build a convent on the site of her temple’s god. Cue Russell letting rip with a flashback to Roman soldiers raping the nuns in front of a cross on which hangs Jesus Christ, with an enormous serpent twined around him.

From an encounter she has with a local, rather thick, copper we already suspect that the exotically clothed Lady Marsh is more than a little bit wicked; but it’s when she picks up a hitchhiking teen Boy Scout that we learn just how not to be messed with she really is. This poor lad is pretty clueless if the truth be told; but as our Sylvia prances around in little else but thigh-high boots even Dumbo Kevin (Chris Pitt) begins to think that he might be in for a good time. Unfortunately the kind of fellatio Sylvia has in mind isn’t geared for making you want more—even if you had something left to want more with.

Later, when Lord D’Ampton asks her: “Do you have children?” we know exactly what she means when she replies: “Only when there are no men around.”

Actually she has a great line in dramatic dialogue which alas something usually happens to bring back down to Planet Earth:

“To die so that the God may live is a great privilege. If you know anything at all about history you’ll know that human sacrifice is as old as Dionin himself, who’s every death is a rebirth in a God ever mightier.

“Shit!” [Doorbell goes.]

Of course, all of this carry-on gives Russell, who also does the screenplay, a great excuse to let rip his inner naughty schoolboy—which is never far away in any case. Tramping in from looking at Angus’s excavation Lord James announces: “I love Mr. Flint’s hole; it’s fascinating.” I’m sure it is but I’ll take his word for it.

And doesn’t he have a wonderful time with phallic serpent images? No messing about here. He just batters you over the head with everything from garden hoses to Hoover tubes. Then he’ll throw in a brilliant dream sequence set on a very serpent-like Concorde with Donohoe and Oxenberg fighting over Grant in air hostess uniforms that—of course, it’s Russell—ride up to reveal stocking tops and suspenders whilst the pencil in Hugh Grant’s hand seems to be taking on a life of its own.

Donohoe is a great sport and of course nudity has never been a big deal to this actress; however, Oxenberg had a ‘no nudity’ clause in her contract which unfortunately makes it all seem a bit silly (a bit silly?) when her character Eve is strung up as a sacrifice for the Serpent God. Serpent God, Eve…geddit? Mind you, when you get an eyeful of Lady Sylvia walking toward her, stark naked and wearing the worlds biggest strap-on dildo and look of intent in her eyes you wouldn’t blame her for the industrial-strength looking underwear. Donohoe has another great speech here too:

“Dionin came forth from the Darkness; Dionin dwelt in peace in the Garden of Eden; Dionin gave us the gift of knowledge; Dionin, who suffered the wrath of the False God; Dionin who was trod underfoot by the Son of Man; Dionin, who returned to the Darkness…” To tell you the truth I was beginning to feel a bit bad for poor old Dionin by this point. I guess I’m just an old-fashioned pagan at heart.

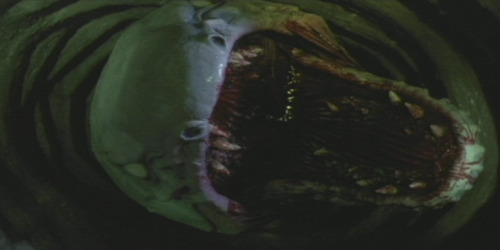

Considering the lack of money that they had I was well impressed when the giant serpent finally put in an appearance. Sure, the head was apparently made from the front of a Volkswagen Beetle but it looked fine to me.

Listen: don’t mind what any film snob tells you. This is a sheer delight. The first time I saw it was in London just after it came out. There were only about five people in the cinema and I don’t think that any of them knew what to make of it. The ideal situation, if you can manage it, is probably at a midnight festival screening where the audience is half drunk. Get enough into you and you might even find yourself dancing in the aisle to the Celtic Rock number ‘The D’Ampton Worm’.

And remember—this blog recommends drinking sensibly!

And here’s “The D’Ampton Worm”, performed by Emilio Perez Machado and Stephen Powys with Loise Newman on violin.

May 27, 2022

Oh man, I love this review as much as I love the film itself! I saw it at least twenty times sinse 1990. “Listen: don’t mind what any film snob tells you.” You just nailed it. It’s a pure pleasure and fuck those poor sould who didn’t get it )