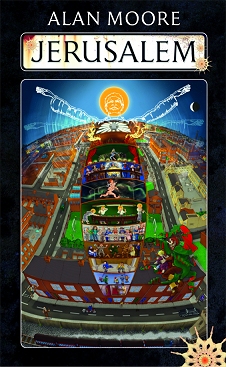

An Abattoir of Poppies:

Alan Moore’s

Jerusalem

“The last word that he said, it was Jerusalem.”

Yeah, I know what he means: I thought it was going to be my last word an’ all.

I seem to have been living with Alan Moore’s ‘million word magnum opus’ for more than three months, including a break to take a trip back home for my dear old mum’s 81st birthday.

Do you remember that episode of Friends where Joey just has to get through all of that Thanksgiving Day turkey? Where he’s worried that one day he’s the guy that can’t finish the turkey and the next he’s the guy who can’t finish the sandwich?

Well, that was me: worrying that one day I was the guy who couldn’t finish Jerusalem and the next day I couldn’t finish a short story.

I hadn’t been quite getting it, you see. Well, not in the beginning at any road.

It’s the kind of book — a very BIG book – that may just contain all the secrets of the known universe, if only we know how to decode it.

Jerusalem, it’s called. And I damned near gave up on it. Yet when you finally put it down — legs trembling, sweat iced on your forehead, eyeballs screaming out No more, brain; no more! – you realise that, in amongst the endless descriptions of walking his Northampton streets, you’ve read something pretty special. In fact, you have read something that possibly contains more wisdom and fascinating insight than anything else you will come across in a long time. You’ll just have to accept that there is a fair bit of mining involved in getting to those nuggets. A fair bit. Jerusalem is around the same size as the collected works of Shakespeare or even one of James Michener’s more ambitious novels…and a page-turner it is not. You’re not going to be lying on the beach at Estaponda del Grotty chortling your way through this one, I’ll guarantee you that.

‘I will not cease from Mental Fight…

If you have read Moore’s debut novel Voice of the Fire (reviewed here) then you will have a fair idea of what to expect, for in many ways that often difficult book is a dry-run for this one. (And characters from it, such as the insane stilt-man, turn up here.) That was simply Moore loosening the shirt and limbering up a bit before getting really stuck into the long history of the Burroughs, the housing estate in Northampton where he grew up.

And despite his honesty about its shortcomings it is obviously a place that he loves to this day. Well, he does still live in Northampton. And he seems to see it as at the centre of a vortex that takes in damned near all of English history, going back to prehistoric times and then forward to include such things as the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, leaving the reader more than a little surprised at just how much has gone on in this spot that I doubt many give much thought to.

In a sense, with this feeling of events circling and spiraling, gaining in significance as the years pass through each other, it is reminiscent of Moore’s ideas for Jack the Ripper’s Whitechapel in his very long graphic novel, From Hell. (And in his mix of writing styles it recalls even more his stunning and brilliant addition to the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen canon, Black Dossier.)

In Jerusalem, however, he takes it to the nth degree. We have not only the past and the present, often intermingling; we also have the living and the dead observing and even interacting with each other; and we have a view of a possible afterlife into the bargain. In fact, the entire second section deals with just that.

‘…nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand…

The novel is split into three books – The Burroughs, Mansoul and Vernon’s Inquest –, with each having eleven sections and the whole bookended by a Prelude and an Afterlude. The titles to these 35 chapters — and very roughly the contents of them — comprise an art exhibition that has been staged by one of the novel’s main characters, Alma Warren. They are inspired by the dreams and nightmares of her brother, Michael. And each section is written in a different style. Just to give you a ‘for example’: the one that deals with Lucia Joyce (daughter of James), who was in a Northampton mental hospital for years and often visited by Samuel Beckett, is completely written in Joycean language.

How successful it is in this regard, I can’t say, never having read Ulysses; but having eventually deciphered several particularly agonizing passages, it was only to discover that they described Lucia and the 60s pop star Dusty Springfield performing cunnilingus on each other, while Patrick McGoohan, dressed as Number 6 from The Prisoner, rides past on a penny-farthing bicycle. Which reminds me, there’s a fair bit of sex in this book and quite a lot of it is of the ‘nasty’ variety.

One of the book’s funniest chapters (yes, Jerusalem is hilarious in parts) deals with Moore’s real-life actor friend Robert Goodman, who must have a great sense of humour, since he is portrayed as a borderline nutter with a rich inner-life as an imaginary Chandler-type private eye, Studs Goodman, possibly from the mean streets of Brooklyn. I found it sidesplitting, with lines that I want to get off by heart. In fact, I’ve already tried out a few but no one laughed. I really have to work on my delivery.

In trying out these different styles, Moore seems to be pushing himself to the limit as a writer (although in truth it can become wearing for the reader) and is possibly emulating a historical hero of his, James Hervey:

“Massively long by modern standards, Hervey’s work apparently shifts in its style and its delivery with each new chapter, hopping from one mode or genre to another and including ‘narrative description, scientific records, inner monologue, anecdotes, autobiography, eye-witness reports, pen-portraits, short stories, sermons, linguistic studies, nature portrayals, journals, poetry and hymns. There is also much in the work that is reminiscent of a modern film script. ‘…His respect for the extravagantly miserable divine is growing by the moment. Studs would like to see one of these modern pantywaists even attempt a work as grand and various as that.”

As incredible as it seems, that pretty accurately describes this novel.

And the book is crammed solid with real-life characters, from Hervey to Oliver Cromwell through Charlie Chaplin and William Blake. Ah yes, Blake. Of course: eternally beguiling and infuriating mystic-visionary (a description that suits Moore himself), Blake’s shadow lies across much of this, which may give you an inkling as to where the title comes from.

It also features a lot of Moore’s own family and friends. His artist wife, Melinda Gebbie, is in there – and bizarrely enough she is the best friend of the Alma character. Despite the sex-change, Alma is – with her ‘finger-armour rings’, dope intake of industrial quantities and general attitude – probably the bould Alan himself.

And he certainly is here in more than one character, all right. I mean, God knows Moore has done enough bitching about comic books and comic book fans in the last decade, but he can’t resist one last (?) go:

“He never looks at comics these days, even though they’ve become fashionable to the point where adults are allowed to read them without fear of ridicule. Ironically, in David’s view, this makes them a lot more ridiculous than when they were intended as a perfectly legitimate and often beautifully crafted means of entertaining kids. At age thirteen, David’s idea of heaven was somewhere that comics were acclaimed and readily available, perhaps with dozens of big budget movies featuring his favourite obscure costumed characters. Now that he’s in his fifties and his paradise is all around him he finds it depressing. Concepts and ideas meant for the children of some forty years ago: is that the best the twenty-first century has got to offer? When all this extraordinary stuff is happening everywhere, are Stan Lee’s post-war fantasies of white neurotic middle-class American empowerment really the most adequate response?”

We get it, Alan; at this stage we really get it. You’ve been growing crankier with the years and you no longer like comic books. You want to be remembered for something a bit more substantial. I also confess to rather admiring the fact that you have fallen out with every major comics company – not to mention your insistence on having your name removed from at least three film adaptations – and now fund your own work.

Yet… how do I put this delicately? Don’t you think that IT’S JUST A SMALL BIT FUCKING RUDE TO DENIGRATE THE ART FORM THAT MADE YOU A MILLIONAIRE AND GAVE YOU THE FINANCIAL AND CREATIVE FREEDOM TO WRITE SOMETHING AS OBSCURE AND SELF INDULGENT AS THE WORK AT HAND?

- Deep breaths and all that

‘’till we have built Jerusalem…

By the close of the long second book, Mansoul, I put Jerusalem to one side while I took a visit to Scotland for the aforementioned birthday of my mother. I was reasonably sure that I would never pick it up again.

Mansoul had been exhausting: often dense to the point of incomprehensibility, it is, in keeping with the rest of the book, beautifully written and with each word chosen carefully; yet it can be overwritten to the point where you are taken completely out of the story and left admiring the craft rather than the content. And I’m not really sure that’s a good thing.

It deals in its entirety with Mike’s experiences as a toddler in the afterworld, when he comes close to choking to death on a sweet. Appearing as a version of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland (well, Moore does say he still likes vintage comics and this was one of the best) Michael joins a group of vagabond children called the Dead Dead Gang. And if you ever doubted that Alan Moore has one of the strangest and most vivid imaginations you ever came across, then 400 pages of their adventures will cure you of that. It is brilliant – but also, as I’ve said – bloody exhausting, there is so much of it.

But…

Whilst in Scotland, my brother Donald and I decided to take a walk through the area that we grew up in and then on down to where we used to play as children. Belmont Crescent was of course so much smaller than I remembered it. And no. 125, where we lived, is certainly being looked after by whoever is there now.

We went down to the burn – the small stream – and walked all the way along it, going through the old tunnel and out onto the road to Alloway. We were oohing and ahhing as memories came back; and I was actually searching through the trees, as if the old rubber tyre that we used to swing from would still be there. Then Donald said: ‘Do you know, it’s nearly half a century since we were here?’

And that is when I ‘got’ what Jerusalem is about. Well, partially about.

It’s the idea that all those versions of ourselves that we have been still exist somewhere in Time. When the 58-year-old me was walking down that impossibly narrow Belmont Crescent, the 8-year-old me was still kicking a football up and down the enormous version of it. A gang of us in 1967 were still laying jumpers on the road to act as goalposts, whilst in 2017 cars sped unheedingly through them.

Everything was inextricably mixed up and intertwined; and it always had been and it always would be.

When I got back, I picked up the third section – Vernon’s Inquest – and I read it right through.

‘…in England’s green and pleasant land.’

Moore chooses as the epigraph for Book Two, a quote from H. P. Lovecraft’s poem-cycle, Fungi from Yuggoth:

It moves me most when slanting sunbeams glow

On old farm buildings set against a hill,

And paint with life the shapes which linger still

From centuries less a dream than this we know.

In that strange light I feel I am not far

From the fixt mass whose side the ages are.

I’m not sure where I heard the term ‘a mythology for the working classes’ in relation to Jerusalem. I’d like to think that it’s original to me, but I’m pretty sure it’s not. It may even be from Moore himself. Wherever it came from, it’s a pretty accurate description. This is Moore’s ringing declaration of love for the cracked streets of his ‘broken heaven’. And there is a feeling of deep affection, even for some of the more out-there members of his family, thinly disguised and sometimes not even disguised at all.

Like the relative who threw away a fortune because he couldn’t stay out of the pub for two weeks and is referred to as having a super-power: the power to not have any money. Unlike being able fly or see through girls’ clothes it doesn’t seem like much of a power to the young Alan.

And he is able to find humour in even the darkest situations. Like with yet another relative, dog-poor, who on one occasion tried to commit suicide by throwing herself off a building that was too low and only succeeded in breaking both her ankles. On the second attempt she stuck her head in the oven but the gas ran out and she didn’t have any money for the meter.

There’s a love and an unsentimental nostalgia here for a life long gone that I can relate to.

And Moore appears to have the same loathing for politicians that I’m afflicted with myself. Not just the usual ones, either, like Rictus-grin Blair or Thatcher. He’s also pretty down on councillors; and wouldn’t I love to know what those worthies make of Northampton’s famous son.

In the end, I have no idea whether or not to recommend Jerusalem. All I can say is that I’m glad I read it. If you are going to give it a go, however, then plug yourself into the nearest light-socket, re-arrange your mind and hold on tight to what’s left of your supposed, laughingly-called Free Will.

Because you are in for a hell of a ride.

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Jerusalem

2016

Knockabout Limited

London

Recent Comments