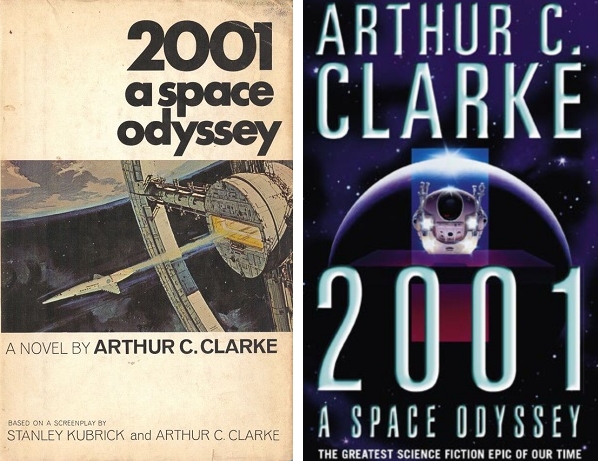

Arthur C. Clarke’s

2001: A Space Odyssey

Based on the screenplay

by Arthur C. Clarke

and Stanley Kubrick

I watched Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey a few months back; and, despite having lost count of how many times I’ve seen it since its release in 1968, I don’t think that I ever found it as deeply satisfying as I did this time around. There is just always something new to pore over. And it changes with age, just as the viewer’s perceptions do.

Sure, it remains as puzzling as it ever was, and still just as open to whatever interpretation you want to put on it; but there is something that draws me back to that film at least once a year. And incidentally, I would consider it one of the most purely spiritual films ever made.

On the other hand, I only ever read the book once – and that was a good forty years ago. So what a pure delight this particular reread was: not at all what I was expecting!

This wasn’t a movie novelization; Clarke and Kubrick wrote it in conjunction with the plotting of 2001, although in fact the film was released a few months before it was published.

If you’re interested enough to read this piece then you almost certainly know the story:

A mysterious alien artifact in the shape of a monolith appears, some three million years ago, to an evolving humanoid species that is on the verge of extinction; and through it the ape-men learn to survive by the concept of using objects as weaponry.

Then, at the dawn of the 21st century, its twin is found on the moon, pointing the way for Humanity to follow its creators onwards to the stars.

This bare outline cannot even hint at the richness that exists in these 250 pages. Evolution, artificial intelligence, trying to comprehend the universe and the soul… There is just so much here.

And as good as the film is, I’m about to cheese off some Kubrick-heads (always a pitifully easy thing to do): the book hasn’t dated in the way that the film has. There you go; I’ve said it. Listen, I know that it remains one of the greatest films ever made but there’s no getting away from the fact that those beehive hairstyles on the space shuttle hostesses give out a whole 60s vibe, man.

Or what about that PanAm logo on the side of the shuttle? Anybody under forty might have a problem believing this, but back in the day it looked as if that company would prove eternal.

Those things are bypassed with the book; and it benefits from the film in that when you are reading certain scenes, you can picture sequences from the movie without it interfering in the slightest. If anything – certainly as far as this reader was concerned – it enhanced the pleasure.

One of the inevitable consequences of ‘film realised as novel’ is that the astronauts of the starship Discovery – Bowman and Poole — are slightly more human than in Kubrick’s icy film. In particular, we get to see Bowman as a more rounded human being.

The depiction of him trying to stay sane as he keeps the ship going on its lonely way to Saturn is masterful and rather moving:

“The ‘Dies Irae’, roaring with ominous appropriateness through the empty ship, left him completely shattered; and when the trumpets of doomsday echoed from the heavens, he could endure no more.

“Thereafter, he played only instrumental music. He started with the romantic composers, but shed them one by one as their emotional outpourings became too oppressive. Sibelius, Tchaikovsky, Berlioz lasted a few weeks, Beethoven rather longer. He finally found peace, as so many others had done, in the abstract architecture of Bach, occasionally ornamented with Mozart.

“And so Discovery drove on towards Saturn, as often as not ringing with the cool music of the harpsichord, the frozen thoughts of a brain that had been dust for twice a hundred years.”

Of course, maybe it’s the limitations of the guy writing this, but I find it hard to put that together with the Bowman of the film.

And the emphasis on the human aspects of the computer Hal are in turn felt less. His presence is not quite as strong on the printed page – although it’s much of a muchness – and we get an explanation of sorts for his psychosis.

Also, not only is Hal explained, but there is an attempt at understanding the motivations of the aliens themselves. And one of Clarke’s mightiest successes here is that they still remain mysterious and essentially unknowable. It is quite a tightrope to walk and he does so with enormous finesse.

I find it a pointless exercise to try to judge the success of a science-fiction novel or film on how much they got correct. I don’t think that many of the really great ones were all that concerned about prophecy. Having said that, though, for a novel written in 1968 and before we had even landed on the Moon, the novel of 2001 feels remarkably fresh. Get a load of this:

“Floyd sometimes wondered if the Newspad, and the fantastic technology behind it, was the last word in man’s quest for perfect communications. Here he was, far out in space, speeding away from Earth at thousands of miles an hour, yet in a few milliseconds he could see the headlines of any newspaper he pleased. (That vey word ‘newspaper’, of course, was an anachronistic hang-over into the age of electronics.) The text was updated automatically on every hour; even if one read only the English versions one could spend an entire lifetime doing nothing but absorb the ever-changing flow of information from the news satellites.

“There was another thought which a scanning of those tiny electronic headlines often invoked. The more wonderful the means of communication, the more trivial, tawdry or depressing its contents seemed to be.”

As it happens, I was reading this on the week that a news site informed the world that Kim Kardashian had ‘bravely’ gone out without make-up. Jeez, you couldn’t make that up.

As the great J. G. Ballard so rightly said, Earth is the truly alien planet.

Recent Comments