Where It All Began:

Arthur Conan Doyle’s

A Study in Scarlet

I would consider three of the 20th century’s great pulp icons (or literary, if it please thee) to be Tarzan, James Bond and Sherlock Holmes. Certainly, Dracula is there also; but he is a child of only one book by his creator and that in 1897. It was down to the cinema to create our enduring group image of the vampire king.

And of course that’s true of Tarzan and Bond as well, although for me the only ‘real’ incarnations of them are in their respective series’ of novels, all of which I’ve read many times over the years. For some reason I never really did get into the Adventures of the Great Detective, bar from reading a couple of stories.

And so, with the noble task of completing an overlooked part of my education in mind, I’ve set myself the challenge of going through the novels and short stories over the next while.

The Scarlet Thread of Crime

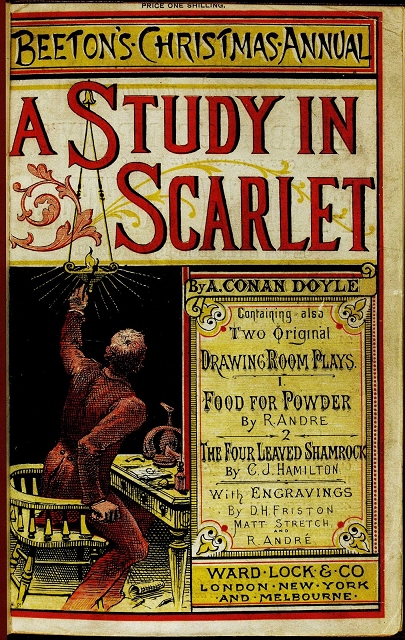

We start – where else? – at the beginning, which was not in the 20th century but in the previous one. It was in fact between the covers of what would be an otherwise forgotten Victorian publication by the name of Beeton’s Christmas Annual of 1887.

From the little I’ve read of A Study in Scarlet it seems that most readers see the structure of this short novel (130 or so pages) as being pretty awful. Which is something that I just don’t get at all. In fact, I find the structure quite fascinating.

Part I consists of seven chapters and is headed: Being a reprint from the Reminiscences of JOHN H. WATSON M. D., Late of the Army Medical Department.

With admirable conciseness Watson tells us of taking his degree of Doctor of Medicine in 1878 before shipping out to serve as a surgeon in the second Afghan war. He is wounded at the battle of Maiwand and shipped back to England where he receives permission from ‘a paternal government’ to take nine months in recuperating.

Since money is getting too tight to mention he finds himself sharing some comfortable rooms with a Mr. Sherlock Holmes at what was to become one of the most famous of all literary addresses: No. 221B, Baker Street.

It takes him a while to figure out just what Holmes does (well, he finally tells Watson) as he is a bit of an enigma. He is incredibly learned in many things — some of them bafflingly obscure — whilst not knowing basic stuff such as the fact that the Earth revolves around the Sun.

“’Well, I have a trade of my own. I suppose I am the only one in the world. I’m a consulting detective, if you can understand what that is. Here in London we have lots of Government detectives and lots of private ones. When these fellows are at fault, they come to me, and I manage to put them on the right scent. They lay all evidence before me, and I am generally able, by the help of my knowledge of the history of crime, to set them straight.’”

Holmes is rather arrogant, to put it mildly, although in fairness he has good reason to be; but his dismissal of others can lead to some amusing exchanges:

“’It is simple as you explain it’, I said, smiling. ‘You remind me of Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin. I had no idea that such individuals did exist outside of stories’.

“Sherlock Holmes rose and lit his pipe. ‘No doubt you think that you are complimenting me in comparing me to Dupin,’ he observed. ‘Now, in my opinion, Dupin was a very inferior fellow. That trick of his of breaking in on his friends’ thoughts with an apropos remark after a quarter of an hour’s silence is really very showy and superficial. He had some analytical genius, no doubt; but he was by no means such a phenomenon as Poe appeared to imagine.’”

When the Scotland Yard detectives Lestrade and Gregson seek out his help in solving the murder of an American visitor to London, it is destined to become the first case for the team of Holmes and Watson. And it is something of a showcase, since the murderer is in police custody by half way through the book.

Way Out West

Part II is headed The Country of the Saints and appears to be the section that ticks most people off. Yet for me it is far more enthralling than the first half.

It goes back to 1847 and begins in that ‘region of desolation and silence’ that the early Mormons had to pass through in order to settle in their Promised Land of and around Salt Lake City. And if you want to take one thing away from this book it’s that Mr. Conan Doyle had a dim view of Mormons. In fact, as the story proceeds that title can be seen more and more to be ironic in the extreme.

The first five chapters of Part II make up an exciting Western yarn, complete with a sinister gang of Avenging Angels and a story of thwarted love. With the merest sweeps of his pen Conan Doyle brought these characters to extraordinarily vivid life.

Who relates the narrative of those chapters, however (barring some omnipresent narrator) I’m unclear on, since they end with:

“As to what occurred there, we cannot do better than quote the old hunter’s own account, as duly recorded in Dr. Watson’s Journal, to which we are already under such obligations.”

After that, the final two chapters wrap thing up nicely.

I’m avoiding looking at Sherlock Holmes timelines – of which I’m quite sure there are many — as I want to try and do my own as I go along. There is a marvelous clarity in this first novel at least, which leads me to place the main events as taking place in 1879/1880.

I think that this short classic deserves to be as famous as it is although I do wonder how many have actually read it. And for me at least, the hero is not the rather unlikeable Holmes, nor even Watson. It is the murderer himself – and with him, Conan Doyle paints the portrait of a remarkable and noble human being: grim, tenacious, and single minded in his pursuit of those who have done a terrible wrong to him and his.

He shouldn’t have been arrested; he should have been given a medal for leaving the world no poorer by removing two walking pieces of dirt completely from it.

Recent Comments