H.P. Lovecraft’s

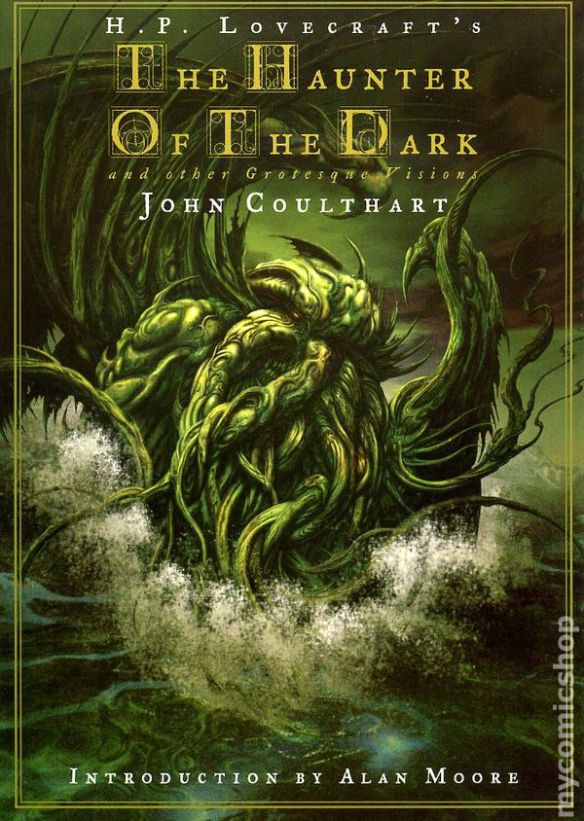

The Haunter of the Dark

and other Grotesque Visions

John Coulthart

An Occasional Look at Lovecraftian Anthologies: 9

H.P. Lovecraft – Haunter Of The Dark

If there were any justice in this old world then the name of the truly gifted artist John Coulthart would trip off the tongue as easily as does that of H. R. Giger for many people. And his work would be just as recognizable.

I doubt that Coulthart takes that view. Judging from the sources he draws his black inspirations from, he no more believes in a universe that is anything but indifferent than did the Pale Prince of Providence himself, author of the stories brought to life in this exquisite little volume and gathering together all his Lovecraftian-inspired pen and ink work between two covers.

The Haunter of the Dark is the earliest, first appearing in 1988. It is the story of writer Robert Blake and his fascination with the church on Providence’s Federal Hill where the Starry Wisdom cult once held their blasphemous rites and where Blake accidentally evokes a manifestation of the Old God Nyarlathotep.

It’s hard for me to tell how successful Coulthart is in adapting Lovecraft’s prose since I’m so familiar with it; but I suspect that some readers who were new to the tale may have had a small problem. What they will not have had any issues with is the artwork, which is simply gorgeous.

If I suspect that they had a problem with this one then I know that Lovecraft virgins will have struggled with the adaptation of The Call of Cthulhu.

In its original form this is of course a masterpiece in so many ways, not least in its unusual yet perfect structure. Most people adapting would struggle with getting across the bleak, cosmic world-view detailed here – and yet Coulthart pulls it off with flair.

The horror of Cthulhu seems to have been diluted in recent years and of late we’ve even seen T-shirts suggesting the Great One as American President in lieu of Trump or Clinton. In fact, you can buy cuddly little fluffy toys in its image. How this strange state of affairs came to be, I have no idea.

What I do know is that Coulthart’s beautiful renderings give us a deity that no one in their right mind would be cuddling: greasy, jagged, beyond enormous, the most indescribable face-tentacles, truly trans-cosmic…stop me, I’m running out of superlatives. This is a great, great piece of work and made last column’s anthology The Starry Wisdom worth buying for alone.

Couldn’t get much better, you might imagine. Except that when I moved onto The Dunwich Horror I thought that I had died and gone to the Lake of Hali.

I have always loved the opening to this story and can quote it by heart (much to the distress of bartenders everywhere):

“When a traveller in north central Massachusetts takes the wrong fork at the junction of the Aylesbury pike just beyond Dean’s Corners he comes upon a lonely and curious country. The ground gets higher, and the brier-bordered stone walls press closer against the ruts of the dusty, curving road. The trees of the frequent forest belts seem too large, and the wild weeds, brambles, and grasses attain a luxuriousness not often found in settled regions. At the same time the planted fields appear singularly few and barren; while the sparsely scattered houses wear a surprisingly uniform aspect of age, squalor and dilapidation. Without knowing why, one hesitates to ask directions from the gnarled, solitary figures spied now and then on crumbling doorsteps or on the sloping, rock-strown meadows…”

Coulthart’s first two pages here capture Lovecraft’s atmosphere to the tee. I felt as if he had opened my head up and plucked out the images I’ve always had of the Dunwich countryside. And the extraordinary thing is that this is uncompleted work, the panels lying empty of text and letting the images speak for themselves. Coulthart writes:

“I was initially reluctant to let go of The Dunwich Horror but had to admit it was becoming a struggle – the epic rendition that The Call of Cthulhu had turned into was proving hard to better and I felt there was little in the pages drawn so far that Alberto Breccia hadn’t covered well enough in his excellent 1975 adaptation… “

When you cop a look at his full page of the demise of Wilbur Whateley, dying and torn on the floor as the dog rips at his non-human insides, you may have cause to argue.

For myself, I’m just happy for the treat that these existing pages give us.

Mr. Moore Adds a Strange Spell

Alan Moore, who needs no introduction himself, does the introduction and I think that it’s fair to say that he was in an odd mood that day. Read it and you’ll get the picture. Well, either that or you’ll be scratching your head.

Likewise with the piece of text that he contributes and which is called The Great Old Ones. As a practicing magician himself he describes the Lovecraftian deities in terms of ‘The Sephiroth of the Qabala, showing the attributions of the Great Old Ones and their descent through the Spheres.’

Thus he does a page of text each on ten major aspects of the Mythos and the full page illustrations that accompany them are no less than magnificent: Yaddith; Hastur; Shub-Niggurath; Azathoth; Yog-Sothoth; Tsathoggua; Yig; Dagon; Nyarlathotep; Cthulhu; Abdul Alhazred.

These portray the Old Ones as they should be: utterly, completely alien. This is the cosmic horror that Lovecraft talked of and he would have adored – quite simply adored – Coulthart’s superb work.

It’s hard to pick a favourite but if I had to have one framed I’d probably go for his deliriously rendered ‘Dagon’, a mesmerizing piece that only becomes fully there after standing back and studying it.

As for Moore’s text, here’s a flavour of his…eh, unusual approach here:

“Nine fathoms slap and lurch above, the layered bedsheet currents hauled indulgently to cover and conceal Her dreaming head, the night-thoughts inculcated by a plunging cold. In vulgar tongue She is CTHULHU, yet the inscriptions of Her terrible divan, reef-vast and starfish-sored, that twice twelve billion tides might not erase, proclaim Her to be great KTHULChU, that her corruption shall be four, ten, and one hundred.”

Now it has to be said that less sensitive souls than Your Humble Narrator have dismissed Moore’s work here as ‘a load of oul’ gibberish’; but as always with this guy, it is well thought out and after a while the very rhythms of the words set up a reaction in the reader, as if Moore is consciously pushing some specific psychic buttons, as he does with his performing art.

On the other hand, maybe he was just stoned.

The Smokestacks of Auschwitz

Unfortunately I could have live quite happily without the final two dozen pages of this collection. They are repulsive full page and two-page spreads that make Hieronymus Bosch’s ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ look like a quiet and restful accompaniment to be enjoyed in conjunction with Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony. They are not based on Lovecraft and are presented with little context for the disgusting images.

A little web search shows that they are from a comics publication called Lord Horror: Reverbstorm that the Manchester counsel banned on the grounds of obscenity.

Amazing; I didn’t even know that happened anymore.

Coulthart explains its inclusion in the foreword:

“It was our intention to consciously elaborate on this unique conjunction of Holocaust architecture and Weird Fiction. Lovecraft and his great predecessor William Hope Hodgson, were to be blended with Lovecraft’ equivalent in our own time, William Burroughs, in Lord Horror’s vicious dreamscape of fascist atrocity, Torenbürgen. Burroughs has always seemed to us to be Lovecraft’s true successor, in sequences like the black fruit from The Ticket That Exploded, offering an equally powerful and uncompromising imagination far beyond the limp pastiches which have so often followed in Lovecraft’s wake. Reverbstorm throws these numerous influences out like a dark prism, flashing broken images of refracted black light: the place where the non-Euclidean geometries of The Dreams in the Witch-House become the fractured visions of Picasso: cities of the Red Night glimpsed in the Night Land, the smokestacks of Auschwitz rising over the Mountains of Madness.

“Sixty years from now, when Stephen King and James Herbert have gone the way of Dennis Wheatley and Seabury Quinn will their books be read as Lovecraft’s are today? – I think not. His work contains essential metaphors for the chaos of our world and the irreducible strangeness of the universe… His work is more vital and relevant than ever.”

And so say all of us.

Mr. Coulthart’s adaptations are a welcome addition to any Lovecraftian’s bookshelves.

Author John Coulthart

Next: An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia & Encyclopedia Cthulhiana

- P. Lovecraft’s

The Haunter of the Dark

and other Grotesque Visions

by John Coulthart Oneiros Books 1999

Recent Comments