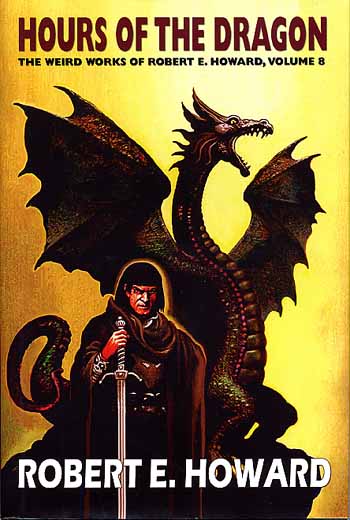

Hours of the Dragon

The Weird Works of Robert E. Howard, Volume 8

Edited by Paul Herman

These ongoing pieces are overviews rather than reviews and therefore contain spoilers galore.

When you take a moment to think about it, in the half-a-dozen or so years after 1928, between them Howard Phillips Lovecraft and Robert Ervin Howard changed the very face of horror/fantasy writing – and the reverberations continue to this day.

Now that sounds like one of those grandiose claims that someone makes when they want respect for a genre that they love. Well, yes, it does deserve at the very least as much respect as any other legitimate art form gets; but to be honest, I’m long past the stage where I could care less about what the non-converted think. And in any case, that opening statement stands true: Lovecraft and Howard changed the entire field itself.

In 1928 HPL saw the publication of his seminal work, The Call of Cthulhu, written two years previously. Until then horror tales had pretty much sustained themselves on a staple diet of ghosts, vampires and werewolves. Such increasingly stale fare wasn’t to Lovecraft’s taste. Instead, he ushered in the nuclear twentieth century with such classics as The Whisperer in Darkness, At the Mountains of Madness and The Colour Out of Space.

It’s impossible to overemphasize the importance of that last one. And if new readers think it feels familiar, it is because it has been imitated so many times. This 1927 story, however, was the primal source of many nightmares to come.

Lovecraft was increasingly interested in presenting his ‘Gods’ not as supernatural beings but as material, extraterrestrial, utterly alien entities – so far beyond us that to use terms such as ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in connection with them was meaningless.

This was a radically new way of doing a horror story. In fact, not to put too fine a point on it, somewhere along the way these had become existential horrors.

A year after Cthulhu, which Robert Howard had praised so fulsomely, extravagantly and – as it turned out – so accurately, he himself presented the world of fantasy with his groundbreaking The Shadow Kingdom. And, again: what must new, modern readers make of it? A feeling that they’re familiar with the themes? Well, when they start to feel like that, then let me remind them that without this story – without Howard — they wouldn’t be enjoying George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire today.

In one short, savage, punch-in-the-face and kick-in-the-nuts of a story The Shadow Kingdom was a yarn that that featured larger-than-life characters set against a pseudohistorical background that contained elements of the weird and the supernatural.

1928 and 1929. Two writers who changed pulp magazine history. And the magazine in which they both appeared and which became their spiritual home? Weird Tales.

There was another writer who deserves to be mentioned as part of the great triumvirate of Weird Tales; but since this introduction has gone on for long enough, I intend to devote a piece to Clark Ashton Smith another time.

The Last Recorded Days of Conan

By 1936 Howard Phillips Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard were approaching the end of the line, both in their lives and in their creative endeavors. In June of that year, Astounding Stories printed HPL’s last great masterpiece: The Shadow Out of Time.

And in five parts – running from December of 1935 through to April of 1936 – Weird Tales presented its readership with Robert Howard’s The Hour of the Dragon.

After more than three years of writing in which REH established the wandering, brawling, wild life of Conan the Cimmerian this is a tale of Conan as the King of Aquilonia, greatest state of the Hyborian Age.

And it would be nice to say that the only full-length Conan novel was perfect. It’s not; but it’s close – it’s pretty damned close.

Conan has been ruling for several years now, but has yet to marry and produce a legitimate heir. And this is something that he is going to regret, since the kingdom is about to fall under a conspiracy that sees a weak, degenerate madman named Valerius take the throne when Conan supposedly dies in battle. This, Valerius is able to do, because he claims some royal blood – and of course because of that lack of an heir.

On the back of the same underhanded maneuverings Tarascus takes the Nemedian crown whilst the general Amalric plays both sides and waits to take over from them. But the real ruler-in-waiting is the hideously powerful wizard Xaltotun, now resurrected from the death he had died three thousand years ago in Acheron – and intent on bringing that evil kingdom back in Conan’s time.

It’s a wonderful, exciting tale that mixes action with a wealth of background for those of us interested in the history and geography of the Hyborian Age. Once again Howard demonstrates that he was and is so much better at this stuff because on some level he really believed in what he was writing. I don’t doubt that for a moment; and it allows him to give us a tightly-plotted, gripping story that somehow manages to be truly epic within only a couple of hundred pages.

As the deposed barbarian takes off on a classic quest for the sorcerous jewel known as the Heart of Ahriman we see how much this man has changed from the brash young thief of his Zamorian days – giving the lie to those half-readers who say that Howard’s characters were two-dimensional.

Amra Once More

In the course of his quest Conan visits some of the scenes of past adventures, most notably when he becomes once again Amra, savage corsair of the Black Coast.

And yet Bêlit, with whom he plundered those shores a quarter-of-a-century before, is never mentioned by name. Perhaps Howard knew it worked better that way, because certainly her shadow lies over his southward return:

“…Conan emptied the wine vessel, tossed it carelessly into a corner, and strode to a nearby casement, involuntarily expanding his chest as he breathed deep of the salt air. He was looking down upon the meandering waterfront streets. He swept the ships in the harbour with an appreciative glance, then lifted his head and stared beyond the bay, far into the blue haze of the distance where sea met sky. And his memory sped beyond that horizon, to the golden seas of the south, under flaming suns, where laws were not and life ran hotly. Some vagrant scent of spice or palm woke clear-etched images of strange coasts where mangroves grew and drums thundered, of ships locked in battle and decks running blood, of smoke and flame and the crying of slaughter…”

One of the things I’ve always loved about the Hyborian Age is that the supernatural elements are never allowed to take over. There is always a sense that life is lived, for the most part, aware of such things only on the fringes of consciousness. It’s not hard to believe that even as adventurous a soul as Conan can go months and even years without encountering the uncanny world. I think that this factor is one of the reasons for the success on television of Game of Thrones with a mainstream audience.

Of course, with Conan, the powers-that-be have now blown film adaptations no less than three times. And as with Tarzan of the Apes, I’m not looking for them to get it right any time soon.

Another thing that I like about The Hour of the Dragon is that Conan is beginning to slow up just the smallest bit. Certainly he makes slips (literally) that I can’t imagine the younger warrior doing. And that’s OK – I have him in his fifties here and so it just lends the whole thing a little more verisimilitude for me.

Here also we see the stirrings of ambition towards creating a continent-wide empire such as Howard hinted at in his famous letter to P. Schuyler Miller and Dr. John D. Clarke.*

The action is vivid and colourful, with the clash of mighty armies being described as only Howard could; and the scenes of Conan riding south through ravished lands are closely observed and stunningly real.

Don’t Throw My Heart into the Dusty Street…

Quibbles are few. Sure, it depends a little heavily on coincidence at times, but what pulp tale of the time didn’t; and these instances were never so serious as to take the reader out of the story. If I had one real problem, it was with the dialogue of Zenobia, who is wheeled on as a deus ex machina and set up as the breeder of Conan’s heir and spare:

“But I am no painted toy; I am of flesh and blood. I breathe, hate, fear, rejoice and love. And I have loved you, King Conan, ever since I saw you riding at the head of your knights along the streets of Belverus when you visited King Nimed, years ago. My heart tugged at its strings to leap from my bosom and fall in the dust of the street under your horse’s hoofs.”

Yes, well…there more; but that’s quite enough of that, unless you want to turn it into a country music anthem. Tugging strings and leaping dust-covered hearts aside, The Hour of the Dragon is a bracing, rousing and marvelous story that would have been an exceptionally appropriate one to end the Conan Weird Tales run with, since it was as far forward in Conan’s life as Howard would take him.

As it happened, however, there was one more major Conan piece to go, returning to his days as a mercenary and freebooting adventurer – Red Nails.

_______________________

Also included in this volume is Howard’s splendid essay, The Hyborian Age. (It appeared in the fan publication The Phantagraph for February, August and October-November, 1936.) He wrote this before he started the Conan tales in order to keep that history and layout clear in his head. For some reason, I mentioned this back in Volume 4. I can’t remember why now, unless it’s because I didn’t expect to still be reviewing these at Volume 8!

I said then:

“…It may be one of the reasons that, despite the supernatural elements and the pseudo history against which he moves, Conan is a very real and believable character. And the essay itself reads like an exceptionally exciting piece of ‘docu-fiction’.”

And so it does. I’m reading an actual history at the moment and it’s rather dry, to put it mildly. Robert Howard would just have to have looked at the damned thing to make it come alive!

Next: Black Hounds of Death

*I’m well aware that in that letter, Howard wrote:

“Conan was about forty when he seized the crown of Aquilonia, and was about forty-four or forty-five at the time of ‘The Hour of the Dragon’. He had no male heir at that time, because he had never bothered to formally make some woman his queen, and the sons of concubines, of which he had a goodly number, were not recognised as heirs to the throne.”

Yet I’ve never felt constrained by it. The Cimmerian did such a huge amount of traveling across his known world that the more time we can give him, the better. And Howard also said: “There are many things concerning Conan’s life of which I am not certain myself.”

And:

“As for Conan’s eventual fate – frankly, I can’t predict it. In writing these yarns I’ve always felt less as creating them than as if I were simply chronicling his adventures as told them to me. That’s why they skip about so much, without following a regular order. The average adventurer, telling tales of a wild life at random, seldom follows any ordered plan, but narrates episodes widely separated by space and years, as they occur to him.”

If Howard had lived to continue to chronicle the Cimmerian’s exploits I suspect that he would have both adapted his 1936 views as well as – and possibly inspired by the interest taken by Miller and Clark – tightened up his chronology.

_______________________

I’ve been lax in not adding an enormous ‘thank you’ at the end of these pieces to the Robert E. Howard scholar, Rusty Burke. For years I’ve loved reading Rusty’s observations and have derived great help from his work when writing my own musings.

Rusty, you’re one of the all-time greats: thank you.

Recent Comments