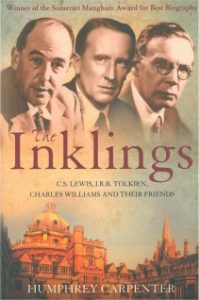

The Inklings

C.S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien,

Charles Williams and their friends

In the absorbing book at hand the author and academic C. S. Lewis is credited as being the main catalyst behind a loose literary Oxford group of writers and teachers in the ’30s and ’40s — the Inklings – whose roughly defined membership included J. R. R. Tolkien; and it seems odd to me now that although I’ve had a lifelong interest in the fantasy field I have only ever had a vague awareness of the group’s existence. This is very likely because even as a child I never read Lewis’s famous Narnia series, having been at that point seduced by what seemed the more robust imaginings of Robert E. Howard and Edgar Rice Burroughs; nor have I ever been able to embrace Tolkien’s Middle-Earth with anything even approaching the wild enthusiasm of so many others.

I feel a lot of admiration for the manner in which author Humphrey Carpenter juggles the backgrounds to so many characters; for in addition to the three main players there are quite a few disparate personalities weaving their way throughout this fascinating account. Indeed, the chief pleasure readers may well find could lie in following up on some of the figures who come and go in the life of the Inklings. Speaking purely for myself, the most fascinating and strangely accessible person here — in a way that that Lewis, Tolkien and Charles Williams simply aren’t – is C. J. Lewis’s brother Major Warren ‘Warnie’ Lewis (and indeed the book is dedicated to him).

He was the older brother by three years; and it is thanks to his meticulous habit of keeping diary records that a lot of what is known about Lewis and the Inklings survive. Indeed, he himself is a fine writer:

“…in came J’s friend Dyson from Reading – a man who gives the impression of being made of quicksilver: he pours himself into a room on a cataract of words and gestures, and you are caught up in the stream – but after the first plunge it is exhilarating.”

Reading an article for The Imaginative Conservative by Bradley J. Birzer, I found myself nodding in agreement at this perceptive description of Warnie:

“…immediately strikes the reader as one of the most intelligent and earnest observers of the last century. Though he suffered from severe alcoholism, bouts of deep depression, and a strange kind of nervousness around the opposite sex, Warnie is loveable at every level. As the reader encounters a man almost utterly overshadowed by his famous younger brother, he finds himself cheering Warnie on, hoping he’ll get his life together.”

Quite. And Lewis himself described his brother in this way to his friend Arthur Greaves:

“…he’s one of the simplest souls I know in a way: certainly one of the best at simple pleasures”.

Touchingly, when Lewis the atheist famously made his conversion to Christianity, he and Warnie – unknown to each other – took Communion for the first time in years on Christmas Day, 1931; CSL was in England, Warnie in Shanghai.

Incidentally, the above-mentioned Arthur Greaves is another of those intriguing peripheral figures who are dotted throughout The Inklings, largely anonymous but something of a fascinating constant in Lewis’s life, often appearing to be a still, calm centre for the writer.

And although it is these minor players that make this book so engrossing, I suspect that many will have picked it up purely for insights into Tolkien. They may be disappointed in that regard, as Carpenter has already written his biography and touches on him to a far lesser extent than he does with Lewis and Williams. It is interesting, however, to see the interaction between these two and to observe on which points their friendship cooled.

- S. Lewis emerges as a far more complex man that I had expected. I simply didn’t know what the hell to make of his lifelong relationship (although it’s far from clear if it was ever sexual) with the much older and rather unpleasant-sounding Mrs. Moore); and when he starts preaching Christianity, with apparent authority on all things related to it, only mere months after discovering it is irritating.

Then there is a mild sort of bigotry which is more than balanced by his works of charity.

One of the undoubted pleasures of Carpenter’s study, however, is to observe these men on their epic walks — travels that recall to mind an England largely vanished; and the undisputed high point for me is the chapter where a Thursday evening meeting of the Inklings is reproduced using the written words of the men themselves. This was risky and could have proved disastrous; instead, it is nothing less than a triumph, leaving me feeling that I had actually been eavesdropping on these remarkable men.

And yet it is Warnie Lewis that I find myself still haunted by – and wishing to know more of — many weeks after closing the covers.

The Inklings: C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams and their friends

by Humphrey Carpenter.

HarperCollinsPublishers 2006 edition

Recent Comments