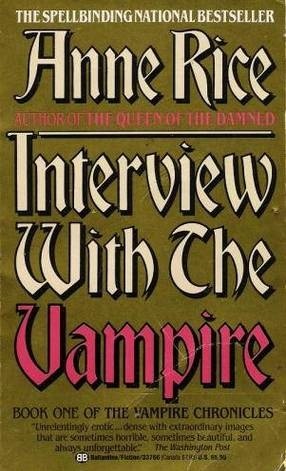

Interview with the Vampire:

Re-assessing Anne Rice’s Modern Classic

I recently took a great notion to revisit this famous horror novel, Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. Back in the day, I had read the first three books in what became known as the The Vampire Chronicles, particularly enjoying this one. By the time I hit the fourth in the series – The Tale of the Body Thief – I had become thoroughly bored with the self-regarding, whining, boastful main character, Lestat; man, had that guy come to utterly depress me. That one I never finished, nor have I gone near Rice’s modern mythology since.

I was of the opinion that she had wound up both her Vampire and Mayfair Witches series’ (eventually comingling them), so it was with some surprise that I saw there was a recent one – Prince Lestat – and it made me curious to see how the original of the species reads today.

Well…not in the same way, that’s for sure; but not for the reasons you might expect, either.

For one thing, it was a bit disconcerting to see that it was first published in 1976. *Gulp*. Back when I was an angst-ridden teenager, in other words. No wonder the two main characters, with all their gloomy existential bullshit, appealed to me.

The story begins in contemporary San Francisco, where a man sits telling the story of his long existence to a teenage boy who is recording ‘lives’ in the hope of getting something good for radio broadcast.

Well, he’s struck gold this time: because Louis was born in 1766 and was a New Orleans plantation owner until 1791, when he was ‘born to darkness’ through the brutal vampire Lestat.

Together they create a vampire daughter in the five-year-old Claudia. They live as a very dysfunctional ‘family’ in Orleans until 1860, at which point Louis and Claudia escape Lestat and spend some years travelling throughout Europe in an attempt to discover where the ultimate vampire source is located.

I did my best to approach this novel with as fresh a pair of eyes as I possibly could, trying to forget previous impressions. And several things went out the window right away.

I’m not too sure now why I always thought of Louis and Lestat as ‘the two gay vampires’ (although possibly Neil Jordan’s excellent film adaptation had something to do with that) but I quickly found that this was way too simplistic. These creatures are non-sexual in the accepted understanding of the word; and yet their feelings of ‘love’ are ramped up to a level that a human simply cannot understand. I can’t emphasise that enough: Anne Rice has created beings so far from humanity (although imitating it) that it is difficult to comprehend their thought processes – which is why they may come across as so boring, depending on your point of view.

If you were to spend immortality in the stultifying company of these two, you would be running out into the sunlight, I’m not kidding.

Far more fascinating for me this time around is the little girl, Claudia. Made into a vampire at the age of five, it is truly appalling to watch as the realization dawns that she will always be this size, this shape.

And it is extremely uncomfortable for the reader in 2015 to have Louis in such close physical proximity with her — sleeping together in his coffin; showering her with caresses; and both of them referring to the other by such terms as ‘lover’ and ‘paramour’.

I doubt very much that I had even heard the word ‘paodophile’ in 1976; but reading these scenes today made me squirm more than a little.

As with seeing the two boyos simply in homosexual terms, however, seeing Claudia as a child is equally incorrect: she is a demon, a stone cold mass killer who just happened to be frozen in time in the semblance of a child. * I found myself moved when Louis recalls a haunting scene early in Claudia’s rebirth:

Grotesque? Touching? I’m not sure; but at moments like this Rice is at her most effective. As she also is with her flowing descriptions of 19th century New Orleans or Paris. In these scenes, away from the gloomy philosophizing of her vampires, she makes the period come clearly to life.

Yet there is just no getting away from the queasy feeling of the scenes with children, especially when Lestat feeds on two angelic seven-year-olds who have been poisoned with absinthe and laudanum. I can only imagine the furore this book would have caused had it been written by a man.

Theatre of Vampires

The most enjoyable thing for me this time around is in noting how much Rice sticks with the conventions of the genre: the mysterious seducer in the cape and fangs; the hunt for the traditional Eastern European vampire; the ‘plague’ on the ship by which they must sail.

And these sit surprisingly easily alongside highly original concepts such as the blood-tears and blood-sweat, or the extraordinary creation that is Claudia herself.

Then of course there is one of my favourites: Paris’s Théâtre de Vampires: a stage whereon the actors are vampires pretending to be humans pretending to be vampires. Delicious!

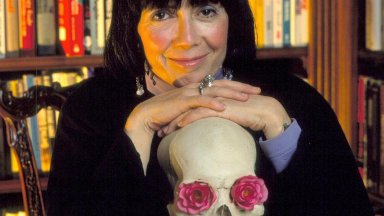

On a more sombre note, it is impossible not to mention that perhaps the reason that Claudia is such a vivid creation is in part due to the death of Rice’s own daughter from leukemia just before the age of six. In the novel, when a human woman is smitten by the ‘child who cannot die’, this is particularly poignant.

And even when I first read this, the descriptions of drinking (even more so later on in The Vampire Lestat) were so aching that I wasn’t at all surprised to discover that the author was a full-blown alcoholic at the time of writing. She quit in 1979.

I’m glad I reread this. In the end, Interview with the Vampire is a deeply melancholic novel and view of the world. And it leaves me with the vision of a demon cast in the form of a child… yet who never really was one, but for five short years.

*Incidentally, in the film she is about twelve years old. As played by a very young Kirsten Dunst, that is disturbing enough. I suspect that, apart from the casting logistics, it would have been just too much for the cinema to have remained that faithful to the book.

Recent Comments