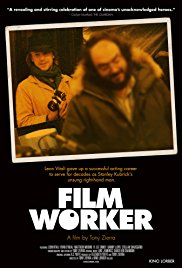

Existing in Stanley’s World:

Filmworker

(2018)

When I first saw Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange I just sat there stunned, thinking that it had to be just about the worst film from a major director that I had ever seen.

When Leon Vitali came to the end credits he said to the person with him that this was the man he wanted to work for.

Different strokes and all that.

As a young film nerd in the ‘70s Kubrick should have been one of the guys on my must-see list. Hell, film enthusiasts adored him. But I never quite got him, not in the way I instinctively ‘got’ Sam Peckinpah or Ken Russell. Or, later on, David Cronenberg. Any one of those three – in my opinion to this day – has ten times the talent that Kubrick had.

And yet…

…two of my all-time favourite films exist because of his incredible, obsessive vision: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and my favourite and most-watched film ever, Barry Lyndon (1975). So I’ve had a complex reaction to him, to say the least.

This engrossing documentary by Tony Zierra looks at a man who seemingly submerged his entire personality and life to work with ‘the Maestro’, as Lyndon actor Ryan O’Neil calls him.

Leon Vitali was a handsome, up-and-coming English actor. Images from the ‘70s show him as rather dashing, handsome and flamboyantly-dressed, something that he surely wasn’t by the time had worked for the Maestro for a quarter of a century. By that time he looked as if he was at Death’s door.

He was spotted by Kubrick and cast as Lord Bullingdon in Barry Lyndon, a role he played with such brilliance that he must surely have been on the verge of becoming a major actor. Yet when Kubrick called him and asked him to work behind the scenes on The Shining (1980) he seems to have been willing to retreat to the shadows, ultimately doing everything for the Maestro, whilst constantly seeking his grudging approval. And all right, I get the whole thing about learning to colour-grade, doing casting and even handling the calls that came in from all over the world, making sure that foreign dubbing and advertising was spot-on. But Stanley calls him up and tells him to clean out a room? He tells him to set up monitors so that he can be in contact at all times with his dying cat?

Are you frigging kidding me?

He was already working 16-18 hours a day, seven days a week, at Castle Kubrick – and then when he got home, exhausted and ready to hit the sack, the phone calls were still coming in from the Maestro. He would work until everyone was gone on Christmas Eve and then the phone would start again at one on Christmas Day.

I honestly don’t know how this man managed to procreate, and yet he has a wife and family. Who must have been living saints to put up with this nonsense.

“Stanley didn’t trust anyone”, says Vitali. “Nobody managed Stanley”. Really? Maybe someone should have tried saying “No” to this bollox once in a while.

Vitali is kept out of sight when Stan the Man is meeting bigwigs; Stan puts Vitali’s name on letters and memos when he’s castigating someone; the Maestro bawls him out in front of people; yet Leon Vitali has an excuse for all of this behaviour.

Mathew Modine says that when he first met Vitali he just assumed that the man was Stanley’s gopher. Gee, I wonder what gave him that idea? And yet I doubt that Kubrick would have gotten anyone, star-struck worshipper of the Genius or not, who would have done the same incredible amount of work or been able to apply such a diverse range of skills, from marketing to cutting world-wide trailers. He even basically finished Eyes Wide Shut (1999) when the Maestro fell off the twig on March 7 of that year. This man deserves our respect, no matter how puzzled we may be at what he spent a large part of his life doing. Total respect.

So I was left flabbergasted when we learn that after Stanley’s death he had to borrow money whilst still keeping on working for him (unpaid), maintaining the legend and the legacy. So… not much left in the will, I take it?

We get a brief look at Vitali’s father, who died when he was eight and who appears to have been a rather volatile and verbally abusive man. Like a battered wife, did Vitali gradually just become drawn into a whole other kind of abusive relationship? I don’t know. I’d like to say ‘be careful what you wish for’ but Vitali seems to have been happy. In a way, this odd coupling reminded me of Eric Fenby and the composer Frederick Delius: there is that same utter lack of ego, that same impression of one man giving everything to another in the name of Art. On travel forms, for Occupation, Vitali even simply writes ‘Filmworker’.

Zierra’s style with this documentary is unfussy and straightforward, working all the better for it, although I would have liked more behind-the-scenes stuff, especially with Eyes Wide Shut. At least it will go a long way to giving Vitali his well-overdue recognition for what he has done.

On the last occasion that Vitali saw Kubrick they had an actual conversation, something they hadn’t done in years. For Vitali’s sake, I’m glad of that. He comes across as a very loyal, sweet, vulnerable and strangely wounded man. I liked him.

By the time he says that he loved Kubrick, we already knew that. But I really don’t think that was reciprocated. I really don’t. After all, Vitali was only a human being, not a dying cat.

_____

“It was in the reign of George III that the above-named personages lived and quarreled; good or bad, handsome or ugly, rich or poor, they are all equal now.”

Barry Lyndon, Epilogue.

Recent Comments